About Will

William Henry Ogilvie was born at Holefield farm, in Sprouston Parish, near Kelso, in the Scottish Borders, on 21st August 1869. He was the second child in a family of eight. His ancestors had been landowners in the Borders for at least three centuries. Relatives still own and live at Chesters Estate, near Ancrum, the base for the family since 1787.

Will’s parents were tenants of the Duke of Buccleuch at Holefield. It was a fair-sized arable and stock farm, requiring six pairs of Clydesdale horses to work it.

The family lived a very happy and busy life there. They were educated at home by a governess, but when the lessons were over, the young Will liked nothing better than to go outside to play and explore, to ride ponies and to join the ploughmen at their work.

At the age of 10, Will was sent as a weekly boarder to Kelso High School and from there was sent to St Michael’s Vicarage in Malton in Yorkshire where Rev DA Firth prepared pupils for entry to private Schools.

At the age of 12, Will was accepted as a boarding pupil at Fettes College in Edinburgh. This was the longest period in his life that he lived in a city. He loved the life at Fettes – particularly the sport.

When he left Fettes in 1888, he returned to Holefield to learn about farming. He had a great year, learning a great deal about stocksmanship and crop cultivation – as well as a great many stories about the Borders – from his father, the farm steward and the farm workers.

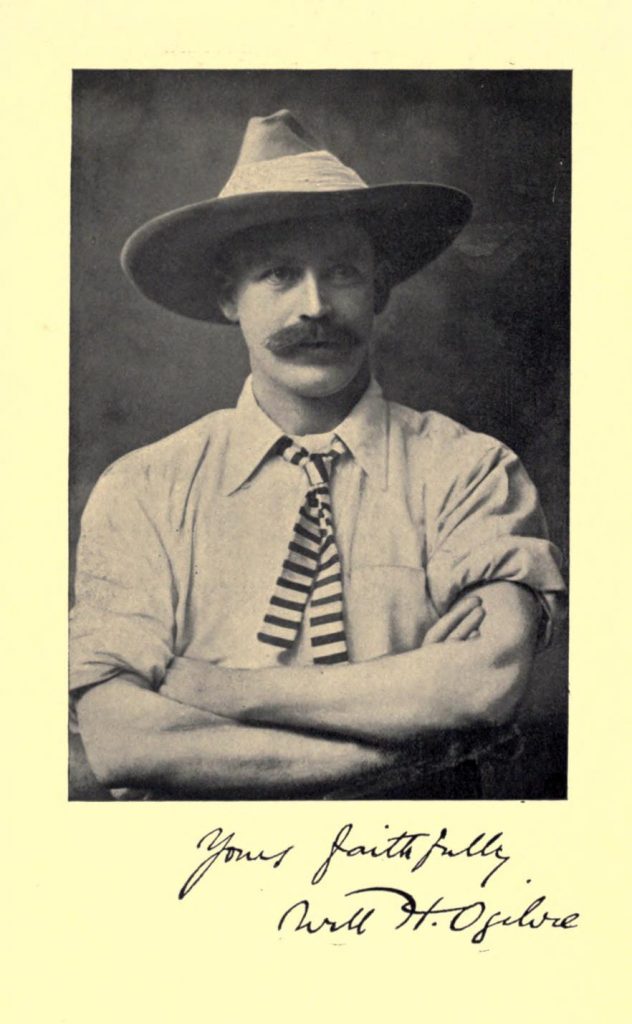

In 1889, just after his twentieth birthday, Will set out for Australia. The plan was for him to go there to mature, learn and gain experience. He went, initially, to work on Belalie sheep station, north of the town of Bourke in northern New South Wales. It was truly outback country. However, he was not without some friendly faces, since the owner of the Station was Mr William Scott, a fellow Borderer, whose brother farmed at Lempitlaw, close to Holefield.

Will worked as a Jackaroo or a shepherd on horseback. He loved the work and riding in the outback countryside. He stayed at Belalie for about two years, latterly acting as overseer. He then moved around, working as a cattle drover, an overseer in a shearing shed, a horse breaker and as a station hand on other sheep stations in South Australia and New South Wales.

It is not clear when he started to write poetry – he won a prize for writing Latin verse when he was at Fettes, and he wrote quite a lot about his early experiences at Holefield – but he certainly was writing regularly while he was in Australia. He wrote about the outback, the life of the folk on the sheep stations, the horses and the characters that he met.

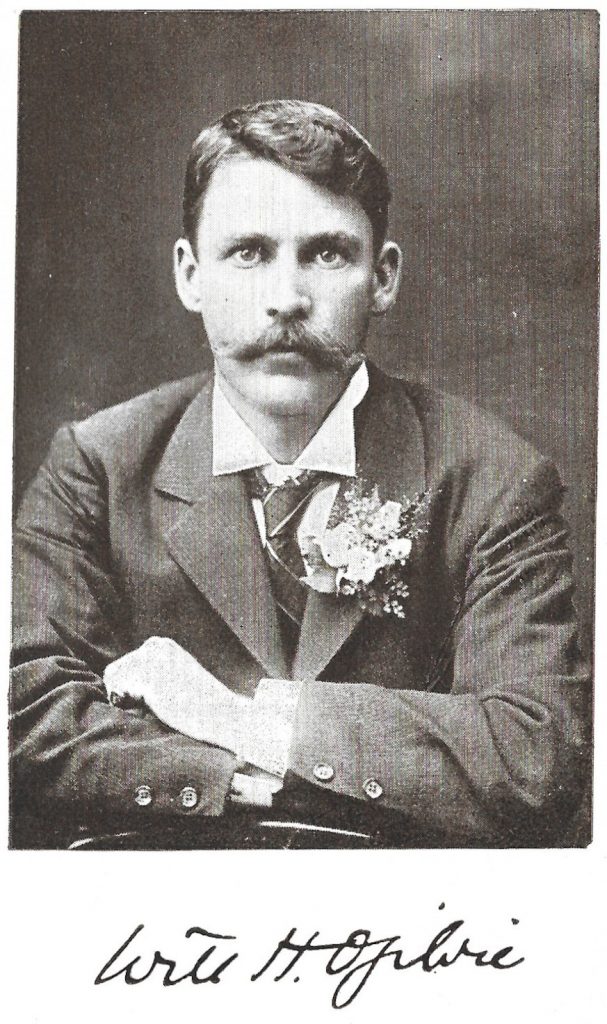

He was encouraged to send some of his poetry to the Sydney newspaper, The Bulletin. In 1894 a poem of his was published for the first time. It was called ‘Beyond the barrier’ and was about a longing for the Outback. In 1898 his first book of poetry, Fair girls and gray horses was published. It was an instant success. Ogilvie, along with Banjo Paterson and Henry Lawson were regarded as the foremost poets of the Australian Outback – they still are.

In 1901, Will left Australia to return to Scotland. He lived in Edinburgh and made a living as a journalist and writer. When his father died in 1904, he returned to Holefield. As the eldest son, it would have been expected that he would take over the farm, but, in his absence, his brother George had been running it successfully and continued to do so. Instead, Will went abroad again in 1905 and took up a post as a lecturer in agricultural journalism at Iowa State College in the USA. However, the academic life did not suit him and he returned to Scotland in 1907.

In 1908 he married Katharine (Madge) Scott-Anderson at Jedburgh Parish Church. They set up home at Brundenlaws, in the village of Bowden. In 1909 they had a daughter, Margaret and in 1912 a son, George. They were a very happy family.

Will had to work hard at his writing to make a living to support the family. During his long working life, he wrote more than a thousand poems. More than twenty books of his poetry and prose were published.

By no means all of his poems have been published in book form. Others are still being discovered in newspaper and magazine archives.

In 1909, he published his major work, a long ballad type poem about the Reiving times, Whaup o’ the Rede. This was heavily influenced by the Border Ballads and the work of Sir Walter Scott.

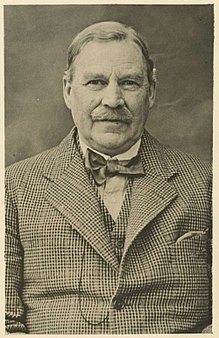

When the First World war broke out, Will, aged 45, volunteered to work in the Army Remount Department, training horses for war. This was a difficult time for him and took a toll on his health.

In 1917 he took the lease of a larger house, the old Free Kirk Manse in Ashkirk, Kirklea, and he was to live there for the rest of his life.

For relaxation, he loved the hills, the outdoors, riding and hunting and being with his family. Friends described him as being a gentleman and a gentle man. It was said of him that ‘he carried with him an air of old-world courtesy such as has now virtually disappeared from the scene.’

He continued working until he was an old man, writing on a wide variety of topics, but mostly concentrating on horses, nature and, above all, the Borders. He wrote some very serious poetry – particularly on the World Wars, but he also wrote others as just for fun and to amuse his children.

As he got older, his memory failed and he lost contact with the world. His last years were spent peacefully and happily at Kirklea.

He died on 30th January 1963. His ashes were scattered on the Hill Road to Roberton, a favourite place of his. He is commemorated in the Ogilvie family vault in the Kirkyard at Ashkirk.

It was on the Hill Road to Roberton, some thirty years later, that a cairn was erected in his memory. He is also commemorated at three sites in Australia.

Will H Ogilvie left behind an anthology of some truly memorable and inspiring poems that are as fresh and as relevant today as when they were written. His words have the power to help us visualise two vastly different rural ways of life. His poems entertain, enlighten, enthuse and move us still.